Stop, pause, slow down or accelerate? What do do next with AI (1/n)

When values come into tension, what do we do? This series explores various decision-making processes and action pathways for the development and deployment of AI out in the real world.

By now, pretty much everyone working in and around this space has heard about the Future of Life Institute’s open letter (many will also be familiar with their AI principles from 2017). Every time I look, the number of signatories grows (it’s important to note that the letter itself, along with the long-termism ideology upon which it’s based, has been heavily criticised).

It might be safe to suggest, at least as of the time of me writing this, that the idea of pausing / slowing down is by far the most popular of proposed options. It aligns to how we commonly think of the deliberative process of moral decision-making (the precautionary principle, ought before can etc.). But it isn’t the only option available to us. Moral analysis can support us in exploring many different pathways forward based on what we believe to be good and right. Importantly it can help us make sense of these values (explicit and implicit), how they come into tension, the ways in which we ‘weight’ these values so that they might be, at times, traded off against one another, and how the process we execute leads to a reflective equilibrium of sorts.

Over the course of this series, I aim to explore issues, opportunities, value tensions, practical considerations and many other topics that I believe - based on over a decade attempting to better understand how to practically design trustworthy technologies and institutions - have real relevance to those involved in research, policy, corporate decision making and practical ML / AI workflows.

I do not seek to assert clear or binary judgements on any of these issues. I’m am not the arbiter of truth, moral or otherwise. In addition, I’m not an ML Engineer or AI Researcher (I refer to my work as ‘practical sociotechnical ethics’). What this means is that I have considerable epistemological limitations, which is true of most of of the world’s knowlege when put into a broad / systemic context (I actually ‘know’ very little). So in my attempt to map, understand and potentially intervene in systems (think of ‘leverage points’) through some type of deliberate effort, I collaborate closely with various leaders in their respective fields. They help erode my ignorance, unpack categorical errors I risk making and help ground my work in an appropriate nuance and specificity.

As of now my intention is to focus on one value, issue, opportunity or practical consideration per post. This is mostly due to the limited time I have to engage in unimpeded writing (my daily Dad workflows make this very tough). I hope it’ll also be useful in making what can be very ‘dense’ a little more approachable.

Let’s begin.

Innovation as intrinsically ‘good’

James Brusseau, a Philosophy Professor from Pace University in New York, published a fascinating and timely, yet deeply controversial paper in late 2022 (controversial in the sense it seems antithetical to most proposals about what we ought to do).

The work immediately piqued my interest. James and I are yet to have a formal discussion about this, but hope to later in the Northern Hemisphere’s summer. I’ve been following and learning from his commentary ever since, so I really do look forward to locking in a time.

The reason I call this specific paper to attention in the focus of this post is that, as most of the world is encouraging the stop / pause / slow down message, James is encouraging the acceleration message.

In a follow up to this paper on Medium, James specifies 5 values and attitudes guiding this position:

Uncertainty is encouraging. The fact that we do not know where generative or linguistic AI will lead is not perceived as a warning or threat so much as an inspiration. More broadly, the unknown itself is understood as potential more than risk. This does not mean potential for something, it is not that advancing into the unknown might yield desirable outcomes. Instead, it is advancing into uncertainty in its purity that attracts, as though the unknown is magnetic. It follows that AI models are developed for the same reason that digital-nomads travel: because we do not know how we will change and be changed.

Innovation is intrinsically valuable. A link forms between innovation in the technical sense and creation in the artistic sense: like art, technical innovation is worth doing and having independently of the context surrounding its emergence. Then, because innovation resembles artistic creativity in holding value before considering social implications, the ethical burden tips even before it is possible to ask where the burden lies. Since there exists the positive value of innovation even before it is possible to ask whether the innovation will lead to benefits or harms, engineers no longer need to justify starting their models, instead, others need to demonstrate reasons for stopping.

The only way out is through: more, faster. When problems arise, the response is not to slow AI and veer away, it is straight on until emerging on the other side. Accelerating AI resolves the difficulties AI previously created. So, if safety fears emerge around generative AI advances like deepfakes, the response is not to limit the AI, but to increase its capabilities to detect, reveal, and warn of deepfakes. (Philosophers call this an excess economy, one where expenditure does not deplete, but increases the capacity for production. Like a brainstormed idea facilitates still more and better brainstorming and ideas, so too AI innovation does not just perpetuate itself, it naturally accelerates.

Decentralization. There are overarching permissions and restrictions governing AI, but they derive from the broad community of users and their uses, instead of representing a select group’s preemptory judgments. This distribution of responsibility gains significance as technological advances come too quickly for their corresponding risks to be foreseen. Oncoming unknown unknowns will require users to flag and respond, instead of depending on experts to predict and remedy.

Embedding. Ethicists work inside AI and with engineers to pose questions about human values, instead of remaining outside development and emitting restrictions. Critically, ethicists team with engineers to cite and address problems as part of the same creative process generating advances. Ethical dilemmas are flagged and engineers proceed directly to resolution design: there is no need to pause or stop innovation, only redirect it.

Each of these requires its own post (perhaps many). And I intend to explore that. But for today, as per the focus of this post, let’s dive into the second.

Before asking whether or not innovation is intrinsically good and why (and therefore whether the burden of proof should shift from where it exists today to where James supposes it could be), it might be helpful to define terms. What do we mean by innovation?

Back in 2014, Horace Dediu published ‘Innoveracy: Misunderstanding Innovation’. At the time I read with keen interest, engaged in some back and forth with Horace and eventually built upon the characteristics he had defined (in effect, to add ‘moral layers’. More on this to come).

So per this work, we might describe innovation as something “new and uniquely useful”.

Horace doesn’t quite seem to make this argument, but I’d like to propose that innovation satisfies all four criteria (new, valuable, unique, useful), rather than just the first and last. This is important because there is much we might argue has limited usefulness in the sense of what is typically thought of as practical utility, but may be deeply valued/valuable. This gets into messy territory if we start talking about something like love, so I’m gonna skip over this now for the sake of brevity.

Assuming innovation satisfies the four criteria above, I reckon there’s a pretty strong argument to suggest that innovation is intrinsically valuable. But, this lacks nuance. For instance, we should probably be asking questions like (a brief, non-exhaustive list):

Valuable for whom?

Useful for whom?

If valuable and useful combine to deliver benefits, material or otherwise, how are those benefits distributed? Do they narrow or widen inequities?

If valuable and useful for one party is associated with or directly causes significant detriment to another party (including biospheric systems and sub-systems), can it possibly meet the criteria for innovation? (The question here is important as one could pretty comfortably argue that anything causing harm to the biosphere lacks utility as we all require a functioning biosphere to live healthy, dignified lives. This is a huge area of inquiry in itself)

Who gets to decide what is useful (and therefore, what problems the innovations solves)?

Etc.

When we get into this stuff, we might come to realise that innovation as intrinsically good is walking on somewhat shaky ground.

We might then extend the taxonomy a little by saying that the innovation ought to be ‘positively purposeful’. In this case, the positive purposefulness guides the exploration of something new, valuable, unique and useful.

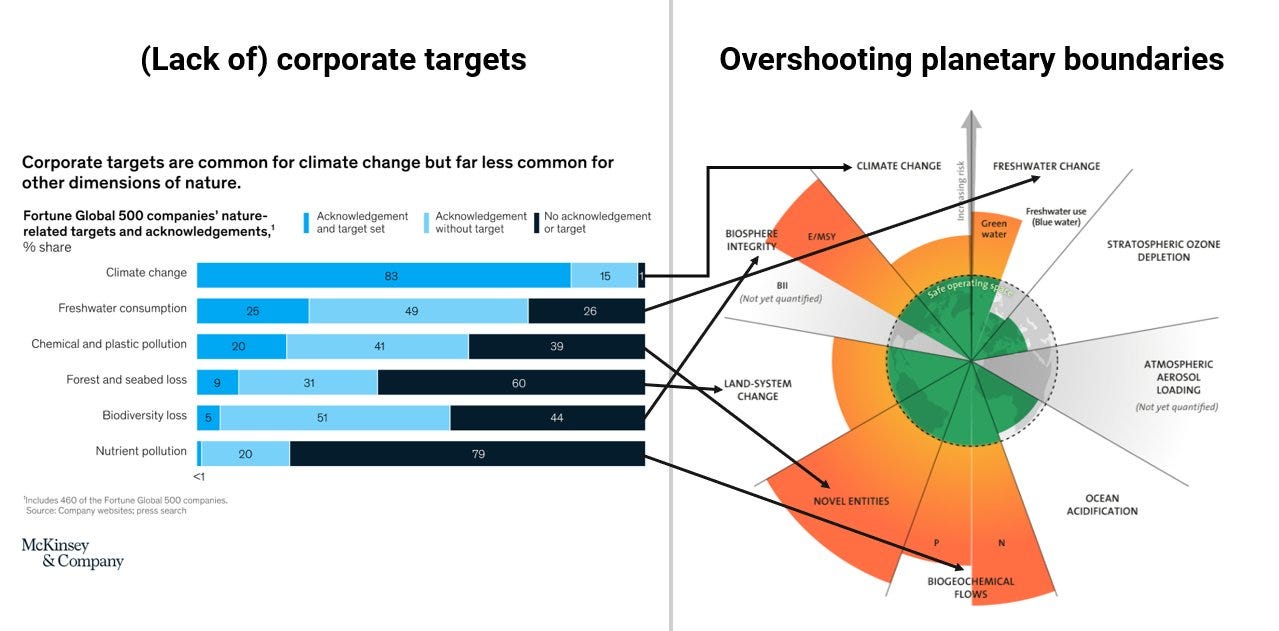

But even here this positive purposefulness would need to be described. In this case we might describe positive as something that aligns to a set of values and principles (when it comes to AI Ethics, most principles fit fairly neatly into Principlism; respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice). But then, which values and principles? Although everyone likely values the biosphere, I’ve seen very few AI Ethics Principles that explicitly focus on earth / climate / ecological science based targets (i.e. bringing the collective of human activities back into the safe operating zone using planetary boundaries).

Some might argue this is our of scope and there needs to be a distinction. Most of my work involves thinking in systems, so I’d politely challenge this.

It’s sort of mess, right? And it’s hard. Really hard.

Also, the stuff I’ve begun to ponder above doesn’t quite get at the point James makes in his follow up article.

Then, because innovation resembles artistic creativity in holding value before considering social implications, the ethical burden tips even before it is possible to ask where the burden lies. Since there exists the positive value of innovation even before it is possible to ask whether the innovation will lead to benefits or harms, engineers no longer need to justify starting their models, instead, others need to demonstrate reasons for stopping.

The idea here is explicitly that artistic expression, creativity, invention and exploring the ‘new’ has value prior to the consideration of moral / social / ecological implications. Because of this, cross-functional teams (which helps capture ‘decentralisation’, if we assume meaningful engagement, and ‘embedding’ at the very least) ought to pursue model development. The burden of proving harm or making the case for stopping / pausing / slowing exists with those critically assessing the work of said cross-functional teams.

I’m still not sure where this lands with me based on my experience designing systems for ethical decision-making within major institutions.

These systems create the conditions for positively purposeful technology discovery and delivery. Over time, once the specific features of the framework are running (like the way the decision-log and knowledgebase interacts with specific tools and workflows), acceleration of high quality ethical decision-making is likely. But it doesn’t necessarily start this way. It typically starts with engaging in a deliberative ethical decision-making processes, which can add time to specific initiatives (note that it doesn’t have to add time to overall projects if you build via a dual-track agile approach. In this case, ethical decision-making can often take place in the discovery workstream that helps feed a more confident direction into a delivery workstream. A lot of this comes down to details of course. All of which I’m happy to expand on if useful).

Rounding this out, I know I’ve solved nothing. That wasn’t the point here today.

What we have done is further explored competing ideas about what we ought to do. This might be useful in itself, but more likely has usefulness because it can better inform the process through which we connect, collaborate and coordinate efforts towards building technology for various forms of good.

To bring it back to the work from James, I’m encouraged by the uncertainty ;)

Until next time folks.

There is a LOT to explore in this area, and here is a good start.