Can we trust AI?

Many conceptions of trust might, from the outset, suggest the answer is no. So let's explore the landscape and ask better, more targeted questions together (time-boxed as always).

This is a question that many folks are now asking (including, of course, me!). Problematically, however, much of the content on this topic likely succumbs to common misconceptions or misunderstandings.

So, before continuing, what do we mean by trust?

Defining trust

Here’s a post with a tad more detail. For now, let me summarise some key points:

Trust is studied in many fields / disciplines

There’s no broadly agreed definition

Many human languages have no direct equivalent for the word

Trust is phenomenological in nature, which means that any explanation is an approximation of sorts (this shouldn’t dissuade us IMO. No global scepticism for me. I mean, we haven’t directly observed certain types of fundamental particles, but we still believe in their existence because of the way our theories match our observations. Important note here, I am not claiming that studying trust is like studying quantum mechanics, so let’s move on before I find myself in deep s&^t)

Trust is most commonly studied in interpersonal contexts, but the literature extends far beyond this

Most conceptions of trust are at least party cognitive (although, other theories exist)

A lot of the trust literature, particularly in the 20th century, centred around prisoner’s dilemma and iterated exchanges. Nicky Case developed a fantastic game (the evolution of trust) if you’d like to explore this

Presently it’s not at all clear if trust in an interpersonal context can be likened to trust in other contexts (say person to organisation or personal to algorithm, or organisation developing algorithm etc.)

As a result of all this and a lot more, we should operate with epistemic humility.

Moving on.

For today let’s consider that:

Trust is the belief that Party A has in the trustworthiness of Party B, within some specific context.

This is a good enough working definition that helps us start the process.

But it begs many further questions, including, what does it mean to be trustworthy? And of course, how does one assess trustworthiness?

Qualities of trustworthiness

Most models of trustworthiness propose something like three characteristics; integrity, competence / ability and benevolence.

I prefer using work from Sutcliffe et al. as it offers more nuance. I’ve found it far more useful in my daily work.

So the idea here is that Party A assesses, based on the best available balance of evidence (within all of the real-world / pragmatic constraints), these types of characteristics. Or in other words, they seek out and assess Party B’s ‘evidence of trustworthiness’.

This leads to a trust judgement (I do or do not trust, to a given extent etc.), which is more than a binary assertion.

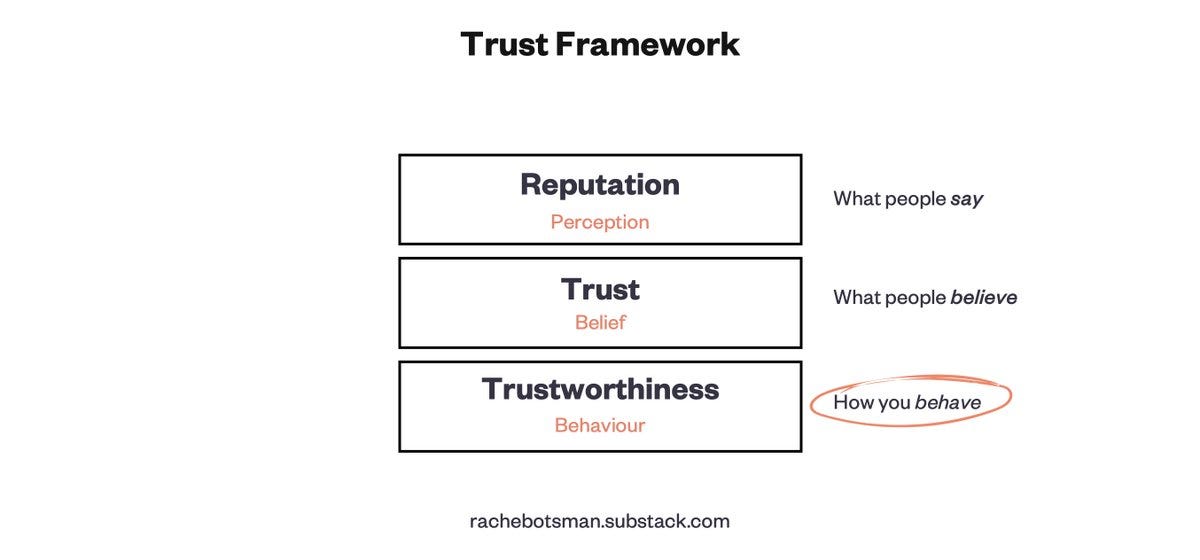

Although oversimplified, Rachel Botsman has created a useful visual to help differentiate trust from trustworthiness (and reputation, which again, is commonly conflated).

Again, before continuing, let me suggest that Party A’s propensity to trust is driven by many factors. We are not homo economicus. We are biopsychosocial creatures who interact with, and develop in relation to the world around us (this can be explored and explained in various ways, from the way beliefs develop through to the way our genes express themselves based on our parents lives of the way we interact with ‘the world’). As a result, it’s thought that our propensity to trust is impacted by everything from social interaction through to ideology, culture and even our DNA (non exhaustive list of contributing factors. Everything is indeed connected).

As to the point above, all this has me operating with a healthy dose of humility daily.

Cognition and constraints

The last little preamble to explore here before continuing are some of the constraints that might impact or limit our understanding of what trust is fundamentally. This is a huge thing, which gets us into the philosophy of trust, including the ontological nature of trust. We don’t have time to dive down that rabbit hole today, but here are two papers (1 and 2, the second focusing on ontological reflections of trust in science. Clearly an important issue in 2023) that may interest those of you with a bit more time to dedicate to this (there is of course a lot of literature on this topic. The two mentioned are far from exhaustive).

Let us instead focus on the ‘weighting’ we give to cognition. By cognition I mean “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses.”

Prior to ‘modern’ neuroscience (all neuroscience is modern really), I feel pretty comfortable suggesting that our belief (academically, not in a popular sense) that trust was largely cognitive was a decent one. It was a darn good educated guess.

Why?

Well, Party A seemingly engages in a mental action or process that leads to some level of understanding. This process that produces understanding or knowledge is based on thought, lived experience and sensory data.

This nicely describes our working defintion of trust from above. It just feels like it makes sense based on our relationship to the phenomenology, the ways in which we had previously studied this etc.

But, this now seems like an oversimplified picture. It’s likely that there’s an automaticity to trust (at least in certain contexts), perhaps followed by what seems like thought, experience and sense data (interaction with evidence of trustworthiness in a broad and somewhat representative sense) informing a mental action / process (assessment of trustworthiness leading to a trust judgement) that leads to understanding (the trust judgement itself, which, based on where this exists along the spectrum of trust states, informs various behaviours of cooperation, risk taking and relating more generally). In other words, post-hoc rationalisation.

An example to highlight this comes from NYU researchers back in 2014. They designed a pretty interesting study (methodologically) that seemingly suggests our brain’s make trust judgements prior to actual awareness.

So in this case there’s a very different process occurring that we might argue isn’t in fact mental (it’s neurochemical/biological, so our theory of consciousness / what the mind actually ‘is’ impacts the claim we make here. Maybe this is explained partially by IIT, biological naturalism or new(ish) work based on the Penrose-Hameroff theory? I’m gonna leave it at that for now. Epistemic trespass risk for sure). It must be informed by sensory data (albeit very quickly), given the face is visible for a micro second (then ‘masked’ of course). And it does lead to some type of understanding (at the level or the organism, and not something we are ‘consciously aware of’) or ‘embodied knowledge’ that can be acted upon.

Mind blown…

Oh, and let me add quickly to this that there are clear epistemological limits when it comes to a person ‘trusting’ an organisation or algorithm. This is very different to assessing the trustworthiness of another human. There’s huge information asymmetry. There’s a very real resource and power imbalance. The unknowns are too significant.

This is why many scholars argue for distinctions. An everyday person cannot know enough about an organisation to thoughtfully assess their trustworthiness and act based on the belief they establish.

Now, I could wax poetic about these topic for a while. They’re all fascinating (IMO) and worthy of exploration. But, you’d be justified in asking right now, does this matter? Should I care? What can I do, as a researcher, policy influencer, designer, engineer etc., to better understand the implications of the question we framed at the start of this article; can we trust AI?

It’s not about trust. It’s about trustworthiness

If you already got here, congrats!

As highlighted briefly, there are clear limits to our understanding of trust. And guess what? If there is significant automaticity to trust, we cannot ‘control’ that.

So what can we actually do?

As I’ve long argued in the context of organisational design more broadly, we can focus on what it means to be verifiably trustworthy. Hilary Sutcliffe, who I mention above, has recently done some brilliant work that has direct use here (opens as PDF).

The basic idea I am proposing is that you cannot control trust. Trust is something someone else does, regardless of the nuance and specifics of the cause and effect.

What you can do is operate with the very clear intent to design your algorithms, and the organisations that create them, to be verifiably trustworthy. Basically we can argue that they (non-exhaustively) do the following:

They intentionally work in the publics’ best interest (they are, as I’ve previously described when exploring Acceleration AI Ethics, positively purposeful or purposefully positive)

There’s an integrity to every deliberation, conversation, trade off, action and reaction

They are open for interrogation and critical inquiry

They are developed based on meaningful engagement processes that actively include a representative sample of directly and indirectly impacted parties in the design, training and deployment process

The meaningful engagement process you enact helps enshrine justice. It leads to what we might consider fairness

There’s a fundamental respect for all life within the biosphere. Yes, this is absolutely critical. Stop with the BS of externalities. The state and trajectory of the biosphere no longer affords such constrained thinking

The organisation and algorithm actually delivers the value it proposes consistently (competence)

All of the qualities interact with one another in various ways. They are greater than the sum of their parts.

These can be supported by specific principles (most organisations now have them) and enabled by an entire system for ethical decision-making if you choose. I’m not prescribing the specifics of what you ought to do here. I am making an attempt to clarify a common confusion, namely, whether or not can we trust AI.

Anyways, that’s time. I hope that this little exploration of the question helps you step back and ponder different and / or better. Specifically, how you / we can design our organisations and the technologies they develop to be verifiably worthy of trust.