It’s time for a genuinely inclusive approach to ethics

How little e ethics can guide decisions with big E implications.

Ethics is all around us. When we make a decision about what to do and why, considering how it aligns to our personal values, the values within our society and of course, the ways in which it impacts others, we’re engaged in an ethical decision making process.

Sometimes this is quite deliberative. It may feel formal, confronting and even stressful. There’s no clear good or right, so what am I to do? Other times we rely on heuristics (rules of thumb) or basic principles that enable us to make faster decisions. These can feel easier and more natural.

It might be helpful to think of this, the way we as everyday citizens on planet earth engage in such processes, as ‘little e ethics’.

Little e ethics won’t replace Moral Theory or Ethics (yes, with a big E). Little e is, sometimes without even knowing it, directly informed by big E. But, I’m here to argue there is a complementarity. Through my work I’m led to believe that a nice dose of little e ethics can support decisions with big E implications inside the institutions that are, and are likely to continue, having a big impact on the world.

What I’m doing here is beginning to make the case for what I call ‘Participatory Ethics’. Participatory Ethics is an approach to ethical decision making that grounds its deliberation in Moral Theory, yet extends beyond this by actively including the people who will be impacted by a decision, action and its spectrum of consequences in the process of making the decision itself. It’s a genuinely inclusive approach to ethics that I believe can, at a time when more people are talking about the ethics of modern information technologies than ever before, support the process of determining what is good and right.

Given I am ‘operationalising’ Participatory Ethics in my work, I plan to publish frequently (and yes, for those on LinkedIn this’ll mean videos) on the topic for the foreseeable future. Consider this a line in the sand, a conversation starter of sorts. I invite you to engage and interact with, query, challenge my assumptions, share your own experience and through all of the back and forth help move this emerging practice forward.

Let’s dive in.

The problem (or framed differently, the opportunity I envisage)

Without getting into the history of Moral Theory (it’s less than critically important for the purpose of today’s post), lets ground our problem and opportunity framing in the ways that ethical decisions are commonly made within organisations today. Like above, there are big E and (a slightly different type of, relative to the earlier reference) little e decisions playing out frequently within public and private institutions of all descriptions.

Big E decisions are sometimes quite formal, supported or guided by experts and deeply consequential (in the sense they may directly impact what an organisation does or not do and how). We can think of this as something that we might actually call ‘ethics’. Little e decisions occur in the daily workflows of people up, down and across organisational structures. These aren’t commonly referred to as ethics. Nor are they frequently thought of as being ethical in nature.

There are myriad challenges with both approaches. Let’s start with the big E.

Decision making contexts of this nature often play out very ‘high up’ if we consider levels of power and influence through hierarchy. Values may be expressed and explored through this process. If there’s decent maturity, values may be weighted, potential consequences may be explicitly documented, relevant historical decisions from Applied Ethics may be referenced. Through this process, a committee or group of some description may provide documented guidance about what is good and right (in this specific context as a direct result of their deliberation). This information will be weighted against what we may think of as more traditional business decision making criteria (the myriad factors that impact shareholder confidence and value). If all works well it informs what is done, what is not done and how the organisation does what it has selected to do.

This then has to be translated into the daily workflows of designers, engineers, data scientists, marketers, customer support staff and the many, many others involved in the organising structure that brings a product or service to a group of people that (hopefully) benefit from it.

Part of the problem is that there’s little evidence to suggest that an organisation’s published ethical principles significantly impacts how products and services get designed, built and launched (which we can argue includes Generative AI initiatives).

In the past I have referred to this as the ethical intent to action gap (drawing from the intent-action gap described in the behavioural sciences literature). A 2020 study from Sull et al does a reasonable job of highlighting important aspects of this gap, suggesting that there isn’t even a correlation between published values and culture (this is a proxy for the ethical intent to action gap that I’d argue based on experience transfers fairly well).

So, even when good quality ethical deliberation occurs at the ‘top’ of the organisation, there’s a very real risk that it’s watered down or perhaps even missing at the level of the organisation where a lot of the “work gets done”. It’s hard to ‘operationalise’ principles.

This is the top down approach, but what about bottom up? Does ethics have a ‘Slack Effect’ (starts at the ‘bottom’, grows, eventually the whole organisation formally adopts it)?

Recent examples of prominent ethicists within big tech companies speaking out, being fired and having to deal with all kinds of challenges is one leading indicator. Taken alone this might suggest that little e ethics, the processes of deliberation that occur in everyday workflows, amongst cross-functional teams and at the water cooler, has little positive impact. It doesn’t make its way up to those governing the corporation. If anything, this groundswell deliberation may be seen as a corporate risk.

But, as is often the case with any complex adaptive system, this unlikely gives us the fullest, most nuanced picture. So instead of diving down a rabbit hole and for the sake of brevity, I’ll argue from experience that the little e ethics I’m referring to here rarely make their way up into those higher level big E deliberations.

This is not to suggest that the little e, micro ethical decisions don’t directly impact how an organisation operates. They do, massively, and in many ways. For instance, the call that a call center operator makes to try and act based on their values and support someone in need. The engineer who spends additional hours trying to align their product to the principles of Privacy by Design. The product manager who pokes, prods and prompts her team on a regular basis, asking questions that enhance focus towards respecting rights, staying clear of manipulative design patterns in order to achieve certain business metrics and ensuring that certain biases are at the very least challenged. All of this adds up.

Yet in a paradigm of ‘growthism’, in the age of ‘surveillance capitalism’, in a world operating far beyond its ‘boundaries’, we have to ask, is this enough?

How to get started with Participatory Ethics

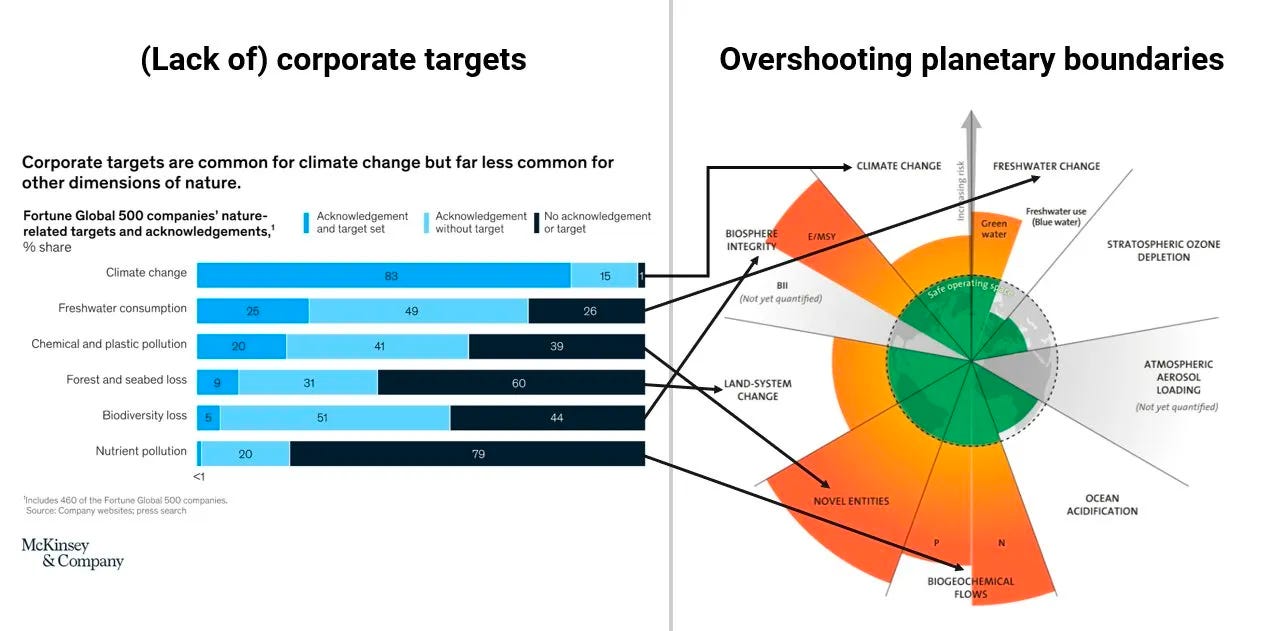

We’ve barely scratched the surface of the landscape (or iceberg?), yet it is hopefully becoming clearer that there is an opportunity to establish a more dynamic relationship between E and e. These are big organisational design challenges. Establishing such a dynamic might require some very hard decisions to be faced with courage. Why? Because there are tensions that exist between directors that have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interest of their shareholders (i.e. to make lots of money and to keep growing shareholder value) and what might be, on balance, morally good and right (i.e. to reduce or eradicate a line of business entirely, as a for instance). When it comes to impact on the environment, perhaps expressed through the planetary boundaries model, this is quite common (Exxon’s overwhelmingly accurate climate predictions anyone...?)

So, instead of changing the whole world today, let’s discuss how you can practically make ethical decision making processes more inclusive.

To start with, I’ll express this as an example. As a result, it will be void of some necessary detail (i.e. the inputs, thoughts and outputs of an ethical decision making system, how they are implemented across an organisational context etc.).

Let’s begin.

You’re a health company doing something new. You want to use NLP (Natural Language Processing) to predict and effectively intervene in ways that limit adverse mental health events. To do this you’ll need to ‘passively monitor’ the conversations that people are having within a certain context (let’s say, as with Lua Health, A University of Galway NLP Lab spinout that I work with, this occurs within the workplace and through a selected chat tool i.e. Teams or Slack).

In the early stages of this process, you engage in an activity to define or refine your organisation's purpose, values and principles. Here we can call attention to The Ethics Centre’s 2018 work on Principles for Good Tech.

You may then conduct a principles assessment where you consider the ways in which this proposition may support or come into conflict with your purpose, values and principles. This may help highlight certain value tensions and encourage focus on some areas over others.

Through this you may believe that, if you do this really well, it’s a darn good thing to do ethically.

But you take it further. You run a consequence scanning activity. This helps you express the spectrum of consequences that may arise from doing what you're proposing. Including:

The strength of each consequence (the magnitude of the effect)

The likelihood of each consequence occurring (assign a probability value)

Whether the effect is intended or united

From this process, using a simple yet specific scoring method, you may have a decent idea of the net consequences that could arise from doing what you are proposing.

Taken together with your purpose, values and principles assessment, this fairly small body of work will give you a decent idea of whether you define this as something that is overall good and right to do.

Again drawing from The Ethics Centre, you may have achieved some sense of Reflective equilibrium.

But, and this is a big but (not like that!), how do you know that your views represent those you seek to benefit? In short, you do not. So it’s time to get out of the building (note that this could have been done from the get go. Most teams are more comfortable leading the process themselves first. That’s why I've highlighted the sequence the way I have). It’s time to do some Participatory Ethics.

Here I’d suggest three activities:

Repeat the purpose, values and principles assessment with some meaningful (ideally representative) sample of target beneficiaries (i.e. users)

Repeat the consequence scanning activity with the same or and different cohort (same sort of characteristics as the first if it’s a second cohort)

Put a prototype of the experience to the test in a simulated setting so you can explore how comfortable and supportive this group of research participants feels outside of a highly speculative context. This is what I’ve often dubbed Social Preferability Research. Here’s how to do it

Taken together, these three activities will generate new data. The analysis of this data should yield insights, specifically relating to whether or not those outside of your team - the people likely to be directly and indirectly impacted by what you are doing - believe that this is both good and right. In short, are they overwhelmingly supportive of this? Is it a problem worth solving? Is it moving in the direction of solving that problem well? Does this align to a broader group of people’s values and expectations? Do they really believe it will net help them? Do they feel safe and respected? Would they happily offer this to their mother (only partly joking)?

Without processes such as this (again, simplified example only), it’s very easy to get caught up in something like the John T Gourville’s 9x Effect.

Basically you overvalue what you’re offering. And this can happen with ethics too. You think what you’re doing is good and right and just. But others, those you intend to design for, may not see it the same way. I can’t tell you the number of times the roadblock of, “what do you mean? We are just innately ethical” has had me stumbling.

By getting out of the building, by inviting meaningful (and ideally ongoing) participation, you can overcome the blockers that limit your capacity to see. You can do plenty of little e work, ground that in some big E work (drawing on specific, well established and well studied Moral Theories), and together produce something greater than the sum of its individual parts.

Now, all of the above is grossly oversimplified. It paints a picture for how you can practically bring the spirit (which is the important part) of Participatory Ethics to life. Thankfully it does this via approaches that most teams, with a little guidance here and there, could execute effectively. And this is exactly what I’d encourage you to do. Give it a try. Stumble a little. Refine your approach. Share what you learn.

Together we can take this conversation forward. Together we can enhance our collective capacity to make decisions about what we should and shouldn’t do, based on what we believe to be good and right.

Enjoy the process. Have fun with it. I’m excited to learn from you.