Stop, pause, slow down or accelerate? What do do next with AI (2/n)

How might a more integrated and less technocratic approach help us align AI to human values and maximise its benefits? My continued exploration of the Acceleration AI Ethics approach

In Part 1 of this series I introduced the idea of Acceleration AI Ethics from James Brusseau. If you haven’t read that post, I encourage you to. It helps set the context for a number of articles to come.

Specifically, I explored the idea that James highlighted in his follow up Medium article that innovation is intrinsically valuable. This was one of five values or attitudes James highlights:

Uncertainty is encouraging. The fact that we do not know where generative or linguistic AI will lead is not perceived as a warning or threat so much as an inspiration. More broadly, the unknown itself is understood as potential more than risk. This does not mean potential for something, it is not that advancing into the unknown might yield desirable outcomes. Instead, it is advancing into uncertainty in its purity that attracts, as though the unknown is magnetic. It follows that AI models are developed for the same reason that digital-nomads travel: because we do not know how we will change and be changed.

Innovation is intrinsically valuable. A link forms between innovation in the technical sense and creation in the artistic sense: like art, technical innovation is worth doing and having independently of the context surrounding its emergence. Then, because innovation resembles artistic creativity in holding value before considering social implications, the ethical burden tips even before it is possible to ask where the burden lies. Since there exists the positive value of innovation even before it is possible to ask whether the innovation will lead to benefits or harms, engineers no longer need to justify starting their models, instead, others need to demonstrate reasons for stopping.

The only way out is through: more, faster. When problems arise, the response is not to slow AI and veer away, it is straight on until emerging on the other side. Accelerating AI resolves the difficulties AI previously created. So, if safety fears emerge around generative AI advances like deepfakes, the response is not to limit the AI, but to increase its capabilities to detect, reveal, and warn of deepfakes. (Philosophers call this an excess economy, one where expenditure does not deplete, but increases the capacity for production. Like a brainstormed idea facilitates still more and better brainstorming and ideas, so too AI innovation does not just perpetuate itself, it naturally accelerates.

Decentralization. There are overarching permissions and restrictions governing AI, but they derive from the broad community of users and their uses, instead of representing a select group’s preemptory judgments. This distribution of responsibility gains significance as technological advances come too quickly for their corresponding risks to be foreseen. Oncoming unknown unknowns will require users to flag and respond, instead of depending on experts to predict and remedy.

Embedding. Ethicists work inside AI and with engineers to pose questions about human values, instead of remaining outside development and emitting restrictions. Critically, ethicists team with engineers to cite and address problems as part of the same creative process generating advances. Ethical dilemmas are flagged and engineers proceed directly to resolution design: there is no need to pause or stop innovation, only redirect it.

At this stage, which is very early in my exploration of this proposal, I’m not even close to ‘there’. Many questions remain unexplored and unanswered. It also contradicts, at least to some extent, much of the work I do building systems for ethical decision-making within large, complex organisations. With that said, my intention is to keep exploring and sharing aspects of that exploration in the hope it has value to people, groups and institutions interested in this space.

I think this inherent curiosity and motivated exploration is important. All of this is sprinkled with plenty of epistemic humility. The warring factions in AI Ethics don’t seem to hold such values. This is, very likely, problematic. Instead of collective betterment, we risk competing in ways that are somewhat unhealthy. This deserves its own exploration, so let’s leave it for another time.

With the recent past lightly covered, today we will focus on decentralisation and embedding. As with the previous post, this is a time-boxed piece of writing. It therefore has to come with plenty of caveats. Nonetheless, I trust it’ll be useful.

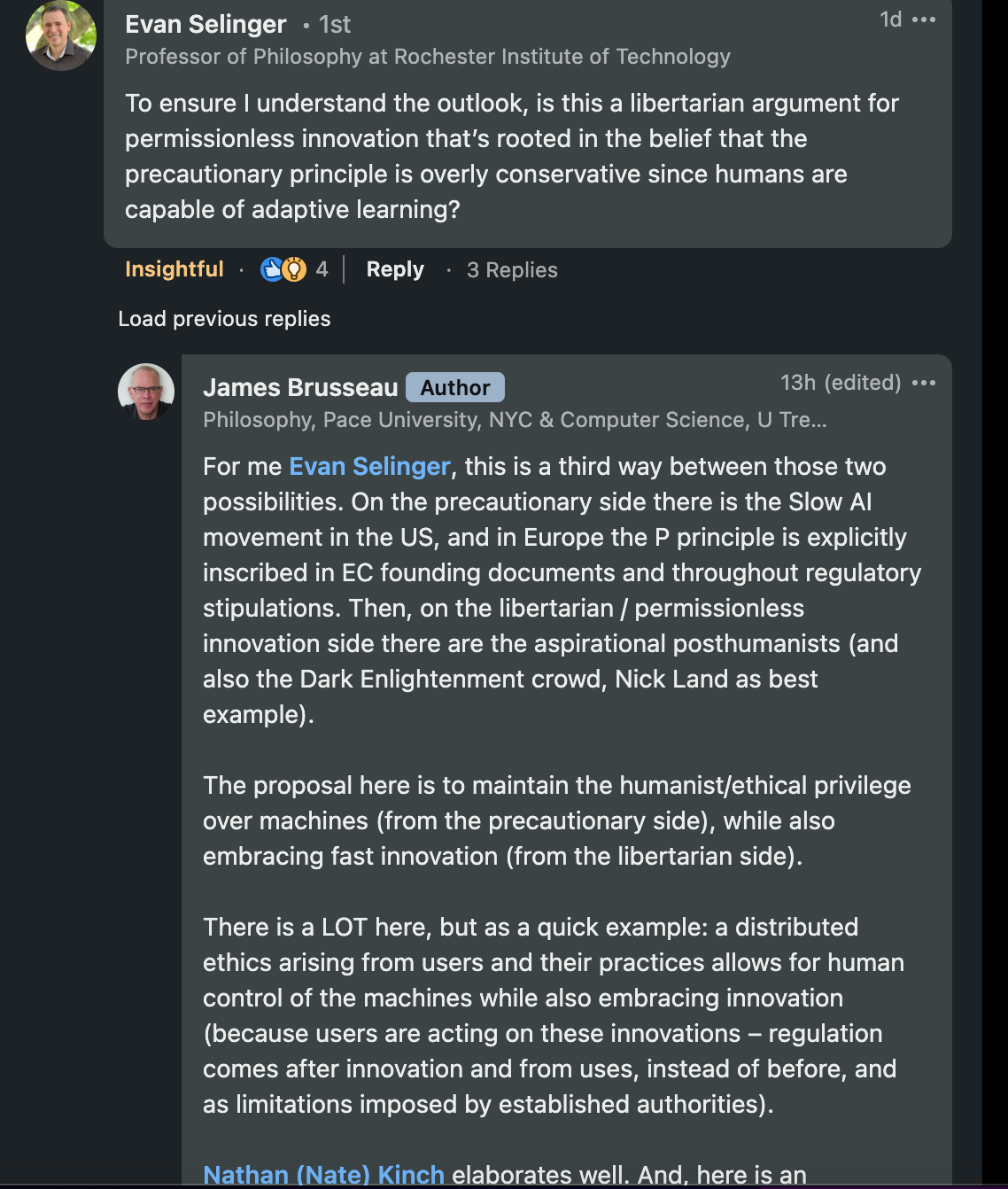

Let me start by briefly highlighting some commentary James recently made in response to a question from Evan Selinger (Evan’s Re-engineering Humanity work is fantastic. Highly encourage you to read that book if you haven’t already).

A little part of me feels this might fall into a technological instrumentalism type paradigm (something The Ethics Centre refers to as one of a number of techno-ethical myths). This may be an invalid assumption (I will clarify through the process of exploring, discussing and refining). With this and a few other uncertainties aside, this commentary helped clarify some of the intent behind Acceleration AI Ethics.

So let’s explore two of the values and attitudes we’re yet to cover; Decentralisation and Embedding.

Decentralisation

The idea of decentralisation is an interesting one. It speaks to me personally. I cover plenty of the why in my late 2022 post. In this post I share some of the challenges I’ve faced throughout my journey. I highlight how, without formal training, I’ve managed to develop a deep capacity to contribute to complex issues at the intersection of human values and technological development (if you want to learn more about my career, there’s a good bit of info here).

Here’s an excerpt that feels relevant:

So what the f%$k do I actually do?

Is it weird that, after seeing this sub-title that I’d pre-written, Liam Neeson’s scene from the first ‘Taken’ came to mind?

Moving on.

I’ve had the privilege of exposure to many different fields, disciplines and practices. I’ve spent my career attempting to integrate them into a practical ‘toolkit’ that I can draw upon to do good quality work in specific contexts.

I’ve built companies. I’ve invested in companies. I’ve helped design data standards. I’ve helped shape data sharing ecosystems. I’ve contributed to a lot of research, some of which is public and some remains within the walled gardens of various corporations. I’ve led organisational transformations. I’ve coached CEOs. I’ve helped launch products. I’ve helped refine products. I’ve built eLearning curriculums. I’ve trained many different professionals around the world.

I’m also a dad. I’m a citizen (in the active sense). I’m a friend. I’m a son. I’m a brother. I’m a community member. I’m a home chef. I’m a practical joker. I’m a shower singer (and actually used to record… Don’t ask). I’m a composter. I’m a coffee drinker. I’m a sunshine seeker. I’m a nature admirer. I’m an explorer of consciousness.

I am greater than the sum of my parts (for those of you who know me well, I hope this particular line lands well. If you get it you get it).

But in this context I am also:

Deeply concerned with and biased towards considered action.

Constantly exploring the cycles of interdependence between society and technology (of course asking myself, how can one possibly separate these things?).

Spending my days helping multi-disciplinary teams align their decisions and actions to their purpose, values and principles.

So, by this description, ‘practical sociotechnology ethics’ kinda works.

In short, I’ve managed to do stuff (for instance, publish research with the likes of CSIRO, lead research programs in collaboration with academics at Northwestern

University, design key aspects of major standards, deliver complex programs all around the world etc.) that would often require a heck of a lot of formal training (most of my peers have doctorate degrees). I’ve struggled with a heck of a lot of issues that you could loosely think of as imposter syndrome (which I recognise has been criticised in various ways from different directions). That’s something I explore here in more depth.

I’m not attempting to big myself up here. This is more about aligning my own experience to the ideas / attitudes / values that might encourage decentralisation as James puts it. It’s also about highlighting the fact I likely have understandable conscious and unconscious biases in this area (my own experience leads to me preferring this type of approach in many cases).

My first-person experience isn’t quite decentralisation, but it certainly challenges aspects of our fairly technocratic society.

Building on this, I’ve long believed that groups, crowds and communities hold and have the capacity to contribute deep wisdom (sounds obvious, but this doesn’t play out much in society). I’ve also long held the belief that ethical decision-making processes are most likely to result in ‘good’ if the people impacted (directly and indirectly) by the decision, action and consequences in question are actively involved in the decision-making process. As a result of this belief I’ve designed mixed method research programs that enable far more equitable decision-making processes.

These ‘get out of the building’ type processes, to draw on Steve Blank (hopefully this speaks to you startup folks), feature heavily in the ethical-decision making systems I help design and implement. They are not necessary for all decision-making contexts. They can and often do induce friction into the process, which can and often does lead to a slowing down (mostly because it’s literally additional work). But, there’s an argument to suggest, as Sandy Pentland and some of his colleagues at MIT have explored, that this could be done via the infrastructure of a Living Lab (if you’re not familiar, check out Social Physics for an intro).

In such a situation this would be integrated into the sociotechnical infrastructure and wouldn’t require additional work. The ‘crowd’ could directly and indirectly contribute to key ethical decisions without additional time and with insignificant burden.

I realise the above, for most, will feel highly theoretical, abstract and perhaps even ambiguous. There’s a huge amount of experience and knowledge backing this approach. I’ll detail much of this over the coming weeks. For now, check out the video below (from my friend and colleague) at about 5 mins onwards (this covers social preferability, along with a simple worked example of the decision-making system that makes ethical decision-making a more active and inclusive process) for more detail. It’ll give you enough for now.

Although what I’m describing isn’t full decentralisation, there is direct values alignment with much of what James suggests. I’d like to argue, and practically explore, the myriad ways in which the work I’ve been doing for years might compliment and even enable the Acceleration AI Ethics approach that James proposes.

More on this to come. It’s an active and ongoing process of discovery.

To wrap up this section briefly, what James seems to propose likely requires a sociotechnical infrastructure that enables some level of decentralised responsibility, governance, issue identification, issue prioritisation, funded collective action etc. I think some version of a Living Lab might be able to support this.

There are many risks with this approach, including those around value neutrality (it’s not super common amongst philosophers, but the idea that tech is ‘values neutral’ is common in corporations and society more generally. This leads to an overwhelming emphasis on use / users and limits designer responsibility. This has been written about extensively, so I won’t get into it now). Counteracting this has been a big part of my work on systems for ethical decision-making. In fact, a scalable version of this system might actually work outside of a single organisation. This is something Mathew Mytka and I have explored for the Consumer Data Right here in Australia. We actually proposed a sociotechnical architecture to the Australian Government. Nothing has happened yet, but here’s to hoping…

Embedding

This one seems overwhelmingly obvious. It’s a huge part of the work I do. In fact, the idea of embedding is directly integrating into the systems for ethical decision-making I’ve now mentioned 4,000 times ;)

Remember pair programming (for all you XP folks)? What about pair design? Well, I’ve built workflows in many different organisations that pair lawyers with designers (for legal design, which, by the way, can have HUGE / positive impacts. This example shows how it effects financial service agreements), ethicists with engineers, social scientists with product managers etc. This helps integrate and embed different and valuable experience, knowledge and skills into technology / model development.

But, we have to be clear that there’s issues with this. The ratio of ethicists to engineers is an obvious example of this. This, the fact that there’s only so many ethicist to go around, is one of the reasons the ethical decision-making systems (4,0001!!!!!) I design have prominent ‘features’ that interact with one another.

The informations flows, workflows, tools, decision logic etc. all interact and interdepend. They enable better ethical decisions to be made at a scale that’s not practically possible given the limited supply of professional ethicists within tech companies (and beyond).

Interestingly, this is where the values of decentralisation and embedding might interact and even come into tension. Overly relying on the professional, especially if there’s sociotechnical infrastructure to support meaningful decentralisation, might induce other challenges. And it might directly inhibit certain directions of innovation (innovation aligned to the taxonomy I build upon in part 1 of this series).

Oh shit! Time is up.

Okay, let me wrap by saying that decentralisation seems to hold huge promise. But there’s significant work to be done. For this to work, my best guess is that we need super well designed sociotechnical infrastructure that supports this approach to responsibility, governance, refinement etc.

Embedding really ought to be stock standard. I do my best to make it so. But it isn’t the only way. We can operate in recognition of various practical constraints and create thoughtful, yet fast paced workflows that benefit from ethical decision-making, with or without the professional in every loop.

As with all of this, consider my musings a conversation starter at best. There’s plenty more to come. I’m learning each and every day and wish to express my gratitude to folks like James, Evan and sooooo many others that help erode some of my ignorance ;)